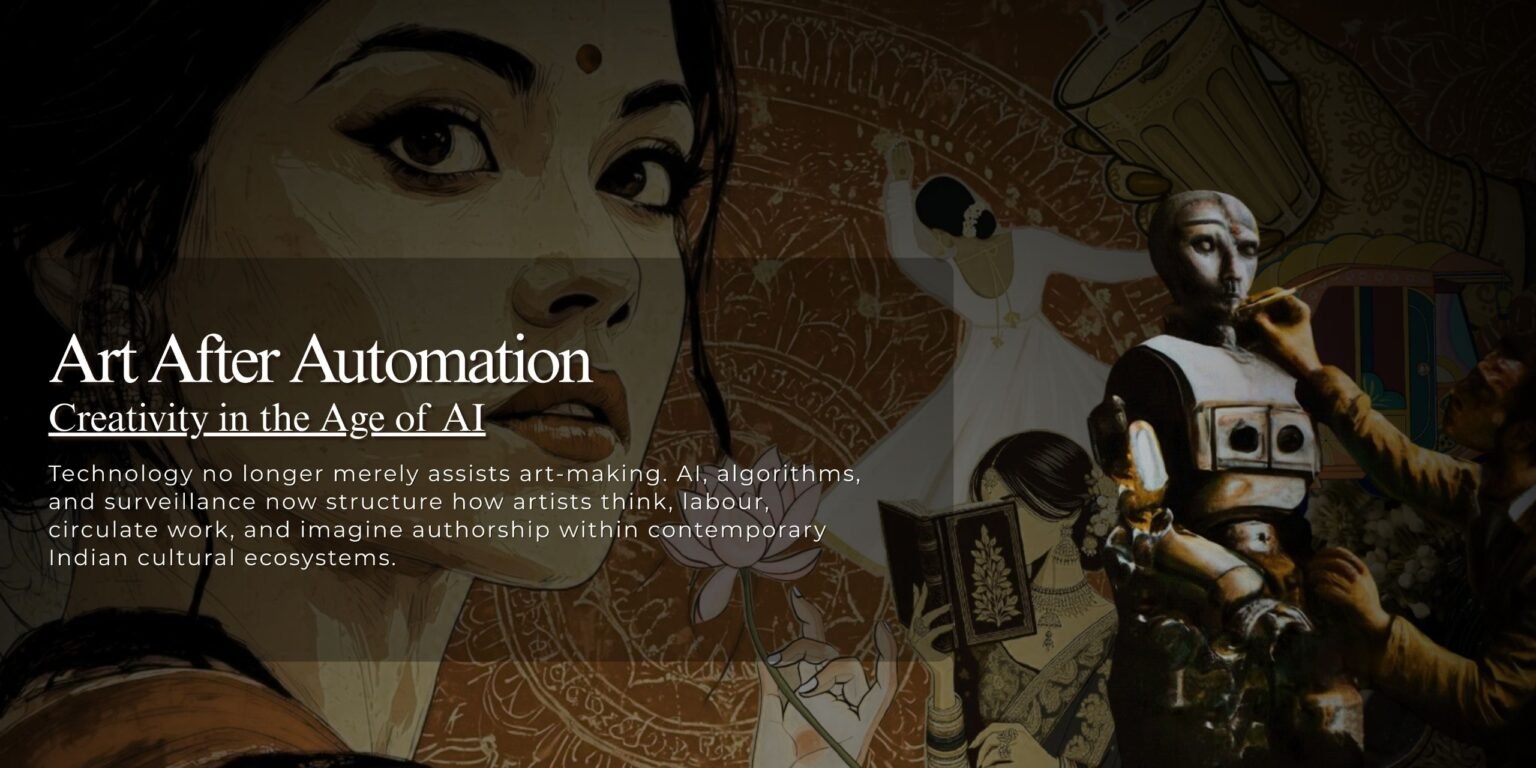

The integration of technology into artistic practice has long extended beyond the adoption of new tools; it has reshaped the very conditions under which art is imagined, produced, distributed, and received. In contemporary contexts marked by artificial intelligence (AI), data‑driven algorithms, and pervasive surveillance infrastructures, technology ceases to be a neutral medium and becomes an active condition framing artistic thought and labour. Nowhere is this transformation more visible than in the Indian artscape, where digital culture intersects with questions of agency, authorship, equity, and cultural identity.

Technology as Structural Condition

Traditionally, artistic technologies, pigment, canvas, sound systems, or film have served as extensions of human agency. However, with the rise of AI and algorithmic systems, the technological substrate itself influences creative decisions in unprecedented ways. Machine learning models, trained on large datasets, are increasingly capable of generating imagery, music, and text that mimic or reinterpret existing cultural forms. Research in computational art demonstrates how neural networks and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are used to produce artworks, sometimes indistinguishable from human‑made pieces. These systems rely on statistical pattern recognition, rather than intuitive, embodied, or contextualized creativity, raising profound questions about the locus of authorship.

In India, this shift coincides with increased digitization and widespread access to AI tools. Artists and collectives experiment with algorithmic processes to reimagine traditional forms, while others critique the techno‑commercial structures underpinning these systems. As a result, the artist’s role becomes entangled with that of the algorithm itself, complicating notions of agency, intention, and originality

Authorship and Originality in the Age of AI

One of the most contested implications of AI in creative practice is its impact on authorship. Historically, authorship has been understood as a human act, rooted in personal expression, cultural situatedness, and the unique synthesis of technique and intent. However, contemporary AI systems frequently produce artifacts that challenge these assumptions. According to interdisciplinary research, generative models trained on vast databases of pre‑existing works can approximate styles and visual languages without human experiential grounding.

This raises challenging questions: When an AI generates an image in the style of Indian miniature painting or an abstract composition evocative of regional sensibilities, who is the author, the human prompter, the algorithm’s developers, or the dataset that implicitly encodes collective human culture? Legal frameworks around copyright and intellectual property were constructed with human authors in mind, creating uncertainty about attribution and ownership in AI‑generated works. In the Indian context, where traditional authorship is already deeply tied to lineage, teacher, disciple transmission, and community recognition, the encroachment of computational authorship further unsettles established systems of value and authority.

Algorithms and Bias in Creative Production

Algorithms do not operate in a vacuum. They are shaped by the data on which they are trained, and data reflects historical, cultural, and social biases. Research in AI art critiques how computational systems often reproduce or amplify entrenched hierarchies, aesthetic norms, and cultural omissive structures. This has significant implications for artists who work with minority or marginalized visual traditions, including Indigenous art forms or vernacular practices that are underrepresented in digital datasets. In India, where folk practices, tribal art forms, and regional visual vocabularies are culturally rich yet unevenly documented online, reliance on algorithmic generation risks reinforcing dominant narratives at the expense of nuanced cultural expressions. Instead of democratizing creativity, such systems may inadvertently privilege styles already prevalent in digital repositories, marginalizing voices that remain under‑digitized.

Surveillance, Data, and the Political Ecology of Art

Beyond creative production, technology shapes how art is circulated and consumed. Data‑driven platforms, social media algorithms, content recommendation systems, and digital marketplaces mediate visibility and valuation. In an Indian digital ecosystem where artists increasingly rely on online engagement for recognition, algorithmic curation exerts considerable influence on what is seen, shared, and valued. These systems often prioritize metrics such as views, likes, and engagement time, potentially incentivizing art practices that are optimized for attention rather than critical depth.

Furthermore, the rise of AI‑powered surveillance, whether in urban management, public security, or digital ecosystems, raises questions about privacy, control, and the conditions under which art can be created or experienced. Although India’s digital surveillance apparatus is structured around governance and law enforcement, the underlying technologies have broader cultural implications. The omnipresence of data collection and analysis conditions how artists represent subjects, particularly when dealing with political critique, personal narratives, or social critique. Individuals and communities may self‑censor in anticipation of algorithmic monitoring or misinterpretation, affecting both content and form

Ethics, Authenticity, and Human Agency

Amid these pressures, ethical considerations come starkly into focus. AI’s capacity to mimic stylistic features invites debates about authenticity and artistic integrity. Critics argue that machines cannot replicate the embodied knowledge, cultural memory, and affective depth that characterize human creativity. The mechanistic logic of AI may yield technically sophisticated outputs, but these can lack the contextual resonance and emotional specificity central to artistic meaning.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that technology can also expand creative vocabularies, offering artists new tools for exploration. Many practitioners emphasize a collaborative approach, where AI augments rather than replaces human insight, and algorithms become a partner in ideation rather than a surrogate for artistic intent. This view acknowledges technology’s productive potential while foregrounding the irreplaceable contributions of human imagination and cultural situatedness.

Forging New Paradigms in Indian Art Practice

In India, these debates are increasingly visible across media disciplines, art education, and critical discourse. Institutions are exploring AI’s potential for cultural heritage preservation, using computer vision and natural language processing to document historic works and expand access to underrepresented art forms.

Simultaneously, artists grapple with balancing technological experimentation and cultural authenticity, asserting agency in a landscape where digital tools are ubiquitous.

Artists and scholars alike must navigate a delicate balance: resisting the reduction of creativity to algorithmic outputs while harnessing technology’s capacity to broaden expressive possibilities. For Indian practitioners, this means engaging critically with the political economy of digital platforms, asserting cultural specificity in globalized ecosystems, and rethinking authorship in an age where human and machine co‑produce meaning.

Creative Agency in a Conditioned Landscape

When technology becomes the condition rather than the medium of artistic practice, it reframes foundational concepts of creativity, agency, and value. In India’s contemporary art scene, situated between deep historical traditions and rapid digital transformation, these issues take on urgent significance. Artists, institutions, and audiences must confront how AI, algorithms, and surveillance infrastructures shape not only artistic form but also cultural discourse itself.

Ultimately, preserving artistic agency in the 21st century requires more than technical literacy; it demands critical engagement with the socio‑technical structures that underwrite creative production. Only by foregrounding human insight alongside algorithmic possibility can the future of art remain vibrant, contested, and deeply human.