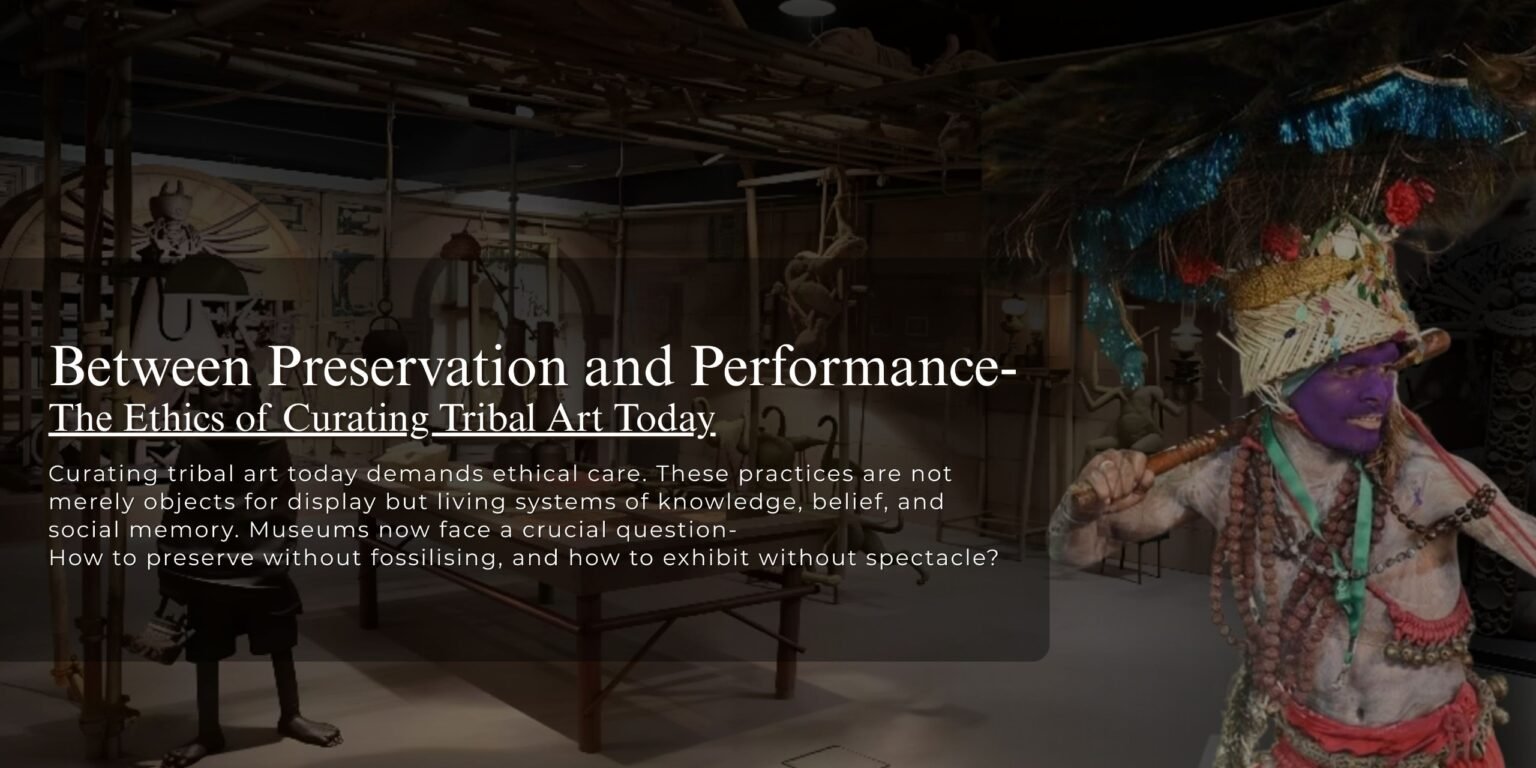

In recent years, the practice of curating tribal art has emerged as an urgent topic in cultural discourse, compelling museums, arts institutions, and curators to confront foundational questions about representation, agency, and the role of art in society. This debate refracts wider concerns about cultural heritage in a globalized world: who gets to define, display, and interpret tribal art, and to what ends? At stake are not only the preservation of tangible artefacts but also the meanings, worldviews, and lived experiences that these artistic expressions embody. In practice, curating tribal art necessitates an ethical sensitivity that traverses preservation, performance, political claims, and community autonomy.

Tribal Art: Beyond Objects to Lived Systems

To engage with the ethics of curation, it is vital first to understand tribal art not simply as objects displayed in museums but as integral components of social life. Traditional artistic expressions such as Gond, Warli, and Bhil motifs embody ecological relationships, cosmological narratives, and aesthetic systems deeply woven into the rhythms of community life. These art forms depict interdependence with the natural world, communal histories, and ritual practices that are inseparable from social identity and ontology. As scholars in art history and anthropology have pointed out, the conventional framing of tribal art through Western museum paradigms often obscures these embedded contexts, treating art as static objects rather than as dynamic embodiments of social memory, performance, and ontology.

This critique echoes broader efforts to resist hierarchies in art history that have historically privileged Western notions of formal aesthetics over Indigenous epistemologies, resulting in reductive and often decontextualized displays.

Museums as Custodians and Interpreters

Across India, institutions such as the Odisha State Tribal Museum in Bhubaneswar and the Tribal Research Institute Museum curate extensive collections of tribal artefacts, from household items and musical instruments to paintings and architectural replicas. These spaces serve as repositories of material culture and also as educational forums where visitors can encounter the diversity of Indigenous communities and their creative traditions. The Odisha museum, for instance, includes life-sized tribal hut reconstructions and multimedia tours in multiple languages, foregrounding both cultural specificity and interactive learning.

Similarly, the Vaacha: Museum of Voice in Gujarat presents a model of curatorial practice in which tribal traditions are not merely exhibited but enacted. Beyond static display, Vaacha’s collections include objects such as musical instruments that are meant to be played and experienced, an acknowledgment that Indigenous artistic forms often resist being frozen as artefacts and instead retain performative and living dimensions.

Decolonizing Curatorial Practice

The ethical challenges inherent in tribal art curation are not limited to presentation alone; they extend to the very frameworks through which museums and galleries operate. Traditional museological norms often derive from colonial logics that separate object from context, privileging expert interpretation over community voices. Contemporary curatorial scholarship, by contrast, urges institutions to adopt participatory and community-centered methodologies that foreground Indigenous epistemologies and decision-making power in the creation of exhibitions. This approach, often referred to as “participatory curation,” positions community members not merely as sources of material but as co-creators of narratives and interpretive frameworks.

International dialogues within museum studies have further enlivened this shift. Ethical frameworks emerging in Indigenous contexts increasingly emphasize consultation, consent, and shared stewardship, a recognition that Indigenous communities hold epistemic authority over how their cultural materials are displayed, interpreted, and contextualized. For example, updated regulations in the United States under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) now encourage consultation with tribal communities regarding cultural materials and ancestral remains, reflecting an ethical imperative toward repatriation and decolonization.

Challenges of Representation and Authenticity

Despite these advances, significant tensions persist. Tribal art often carries complex meanings that cannot be fully captured through museum displays alone. Moreover, power imbalances between institutions and communities can result in misrepresentation or “museumification,” where cultural objects are stripped from their social contexts and framed as exotic or static relics rather than living traditions. Scholars caution against romanticizing tribal culture as unchanging or primitive, a trope that obscures internal diversity and the dynamic evolution of Indigenous practices.

Complicating matters further are socio-political forces that seek to instrumentalize tribal art for nationalist, commercial, or touristic purposes, often at the expense of community agency. Recent anthropological research into Adivasi art and activism highlights how curation can inadvertently become entangled in broader political projects, at times reinforcing dominant narratives rather than amplifying Indigenous voices on their own terms. This scholarship underscores the need for curatorial practices that remain reflexive about power dynamics and resist co-optation by hegemonic agendas.

Collaborative Curatorship and Community Empowerment

Emerging models of ethical practice emphasize collaboration and shared authority in the curation of tribal art. Museums can adopt structures that actively involve community elders, artists, knowledge keepers, and youth in exhibition planning, narrative framing, and interpretive design. Such participatory curation not only enriches the depth and cultural integrity of exhibitions but also fosters a sense of collective stewardship over cultural heritage. Involving tribal voices directly in curatorial decisions can also help address historical injustices and power asymmetries that have shaped museum practices for centuries.

This approach extends beyond physical museums to digital initiatives that document and disseminate tribal knowledge. Projects like virtual archives and community-managed digital repositories democratize access while reinforcing self-representation in the preservation of cultural memory.

Ethics, Performance, and Representation

A particularly complex ethical tension arises when art intersects with performance and living traditions. Artistic practices such as ritual dance, oral storytelling, and ceremonial crafts are inherently performative; they acquire meaning through enactment rather than static display. Curators must navigate how to represent these practices respectfully without reducing them to spectacle or commodifying sacred elements for public consumption. Ethical exhibition design thus requires deep engagement with cultural protocols, community consent, and a commitment to safeguarding spiritual and social values that transcend aesthetic considerations.

Toward Ethical Custodianship

Curating tribal art today demands an ethical sensibility that bridges preservation with performance, object with context, and institutional authority with community agency. It requires a recognition that tribal art is not merely a category of artefacts to be preserved but a living field of cultural meaning, continuously shaped by historical processes, social negotiations, and the creative agency of Indigenous peoples themselves. Institutions that embrace collaborative, community-centered, and context-sensitive practices can begin to address the profound ethical questions at the heart of curating tribal art in the twenty-first century.

In navigating these complex terrains, the ethical curator must continually ask: whose voice is being amplified, whose perspective is prioritized, and how can the representation of tribal art honor the living communities whose traditions it seeks to celebrate?