Among the many Indian modernists who emerged in the mid-twentieth century, Abdulrahim Appabhai Almelkar (1920–1982) occupies a distinctive place. His art embodies a synthesis of meticulous draftsmanship, indigenous visual traditions, and poetic sensibilities that quietly persist in painting histories beyond dominant narratives. Today, revisiting his work invites us to rethink what Indian modernism meant beyond the Progressive artists and abstraction, drawing attention instead to art that situates ordinary life within lyrical pictorial spaces.

A Visual Language Rooted in Indian Heritage

Born in Solapur, Maharashtra, Almelkar began painting at a very young age and later trained at the Sir J. J. School of Art in Mumbai, graduating in 1948. While many of his contemporaries gravitated toward European modernism, Almelkar retained the “Indianness” of his work, drawing deeply from folk traditions, miniature painting, and rural subject matter. His artistic vocabulary emerged from both formal academic training and the visual cultures that surrounded him, particularly the decorative motifs, rhythmic linework, and symbolic lexicon of Indian miniature traditions.

Almelkar’s images are often deceptively simple. At first glance they depict familiar scenes, villagers engaged in everyday acts, tribal musicians at play, fishermen, women at work, and pastoral landscapes. But beneath these motifs lies a woven narrative of cultural continuity, social texture, and human vitality. His figures are not merely representations; they are storytellers, characters in larger dramas of community, labour, and ritual.

Narratives of Everyday Life

One of the recurring themes in Almelkar’s paintings is the rhythms of rural existence. Works such as Three Drummers, held by the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai, depict young boys engrossed in music-making, their bodies animated by the pulsating beat of the drum and the larger community life it evokes. Here, the drumbeat becomes a metaphor for a social heartbeat, connecting tradition, ceremony, and collective embodiment. The detailing executed with rhythmic, bold lines and earthy tones recalls the visual theatre found in folk murals and village art.

Similarly, depictions of fishermen and coastal life reflect not merely economic activity but existential continuity between people and nature. Their silhouettes, often outlined in fine ink over rich washes of colour, resonate with a quiet dignity. Their presence in the frame suggests sustained relationship with environment and craft, a theme far removed from romanticised pastoral nostalgia and very much rooted in lived reality.

Mythic Resonances and Cultural Memory

While much of Almelkar’s work is grounded in the everyday, traces of myth, folklore, and classical motifs permeate his compositions. Untitled drawings featuring figures such as Radha and Krishna in forested landscapes suggest a visual bridge between lived experience and mythic time. Through detailed motifs and compositional structures, Almelkar incubates a deeper cultural memory where the sacred and profane coexist, drawing on Indian narrative traditions without resorting to didactic or literal storytelling.

This interweaving of ordinary and sacred is not accidental. In many traditional Indian visual practices from miniature painting to regional folk murals the secular and the divine are not strictly separate. Almelkar’s brilliance lies in how he translates this ontological overlap into painting, using line and colour to evoke both the immediacy of rural life and the timelessness of narrative archetypes.

Technique as Narrative Strategy

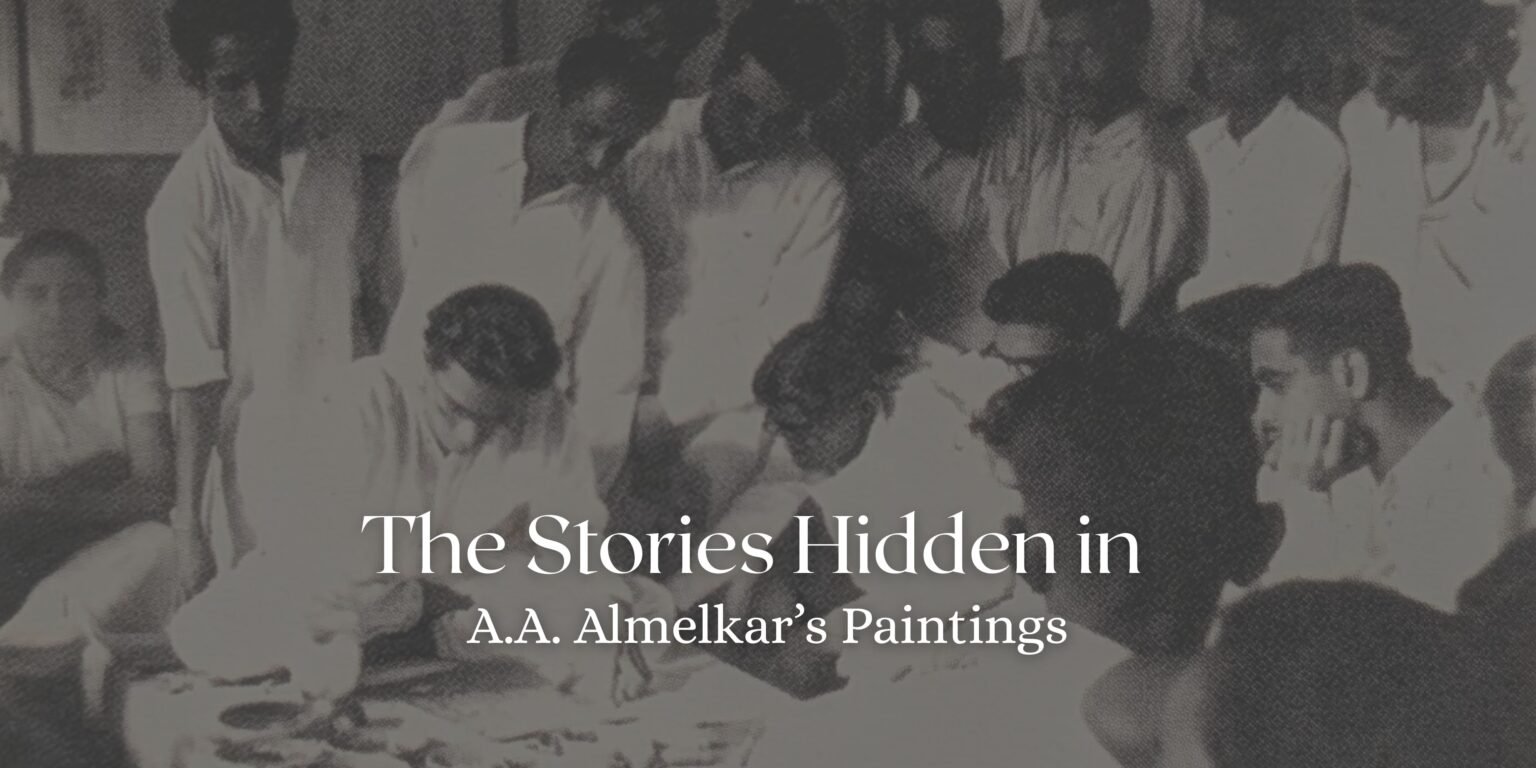

Almelkar’s technique itself is part of the stories his paintings tell. Unlike peers who predominantly used brushes in formal studio settings, Almelkar sometimes applied colour directly with his fingers and employed unconventional tools such as jute, rags, or combs to texture surfaces. This tactile approach lends his compositions a sense of immediacy and material intimacy as though the process of creation is itself part of the narrative fabric.

Moreover, his choice to work on cardboard and paper rather than canvas alone indicates an intuitive responsiveness to the medium that mirrors his responsiveness to subject matter. The textured surfaces and dynamic strokes render his figures and landscapes alive with rhythmic energy, evoking both the tactile presence of folk art and the expressive force of modern technique.

Charting a Distinctive Modernism

In contrast to the Progressive artists’ embrace of abstraction and universal modernist idioms, Almelkar’s work remains anchored in place, both geographically and culturally. His travels through the jungles and tribal communities of India, his engagement with indigenous craft traditions, and his deep absorption in Indian narrative forms produced a visual language that is at once local.

This distinction, however, has also led to his relative marginalisation in mainstream art histories, which often prioritise formal innovation over cultural rootedness. Critics have long noted that Almelkar fought modernism to retain the Indian sensibility in his painting, a commitment that, while limiting his association with canonical modernist movements, anchored his art in a distinct aesthetic continuity.

Legacy and Continued Relevance

Almelkar’s legacy persists in his capacity to make the everyday extraordinary. His paintings are not mere records of rural life; they are composed narratives that compel us to reconsider how art mediates between representation and experience. His finely drawn lines, expressive figures, and harmonic colour schemes invite reflection on human agency, cultural continuity, and aesthetic identity.

Institutions such as the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi and Mumbai hold works by Almelkar, ensuring that future generations may engage with his visual legacy. Critics and curators who view his works today repeatedly describe them as thematic repositories of Indian life, resonating with both the specificity of place and the universality of human expression.

In the evolving discourse on Indian art, Almelkar’s paintings prompt a reconsideration of how stories are carried in form, colour, gesture, and space. They remind us that art can speak not only through abstraction or global idioms, but through the rich textures of local life, tradition, and human intimacy, revealing that sometimes, the most compelling narratives are hidden not in grand gestures but in the quiet rhythms of everyday existence.