Key Takeaways

- Calendar art transformed worship practices from public temples to private home shrines.

- The cow emerged as a potent symbol of Hindu identity during heightened political tensions.

- Mechanical reproduction democratized art and altered the artist’s role.Calendar imagery both unified and divided communities.

- Once avant-garde, calendar art is now regarded as kitsch, overshadowed by photographic reprints.

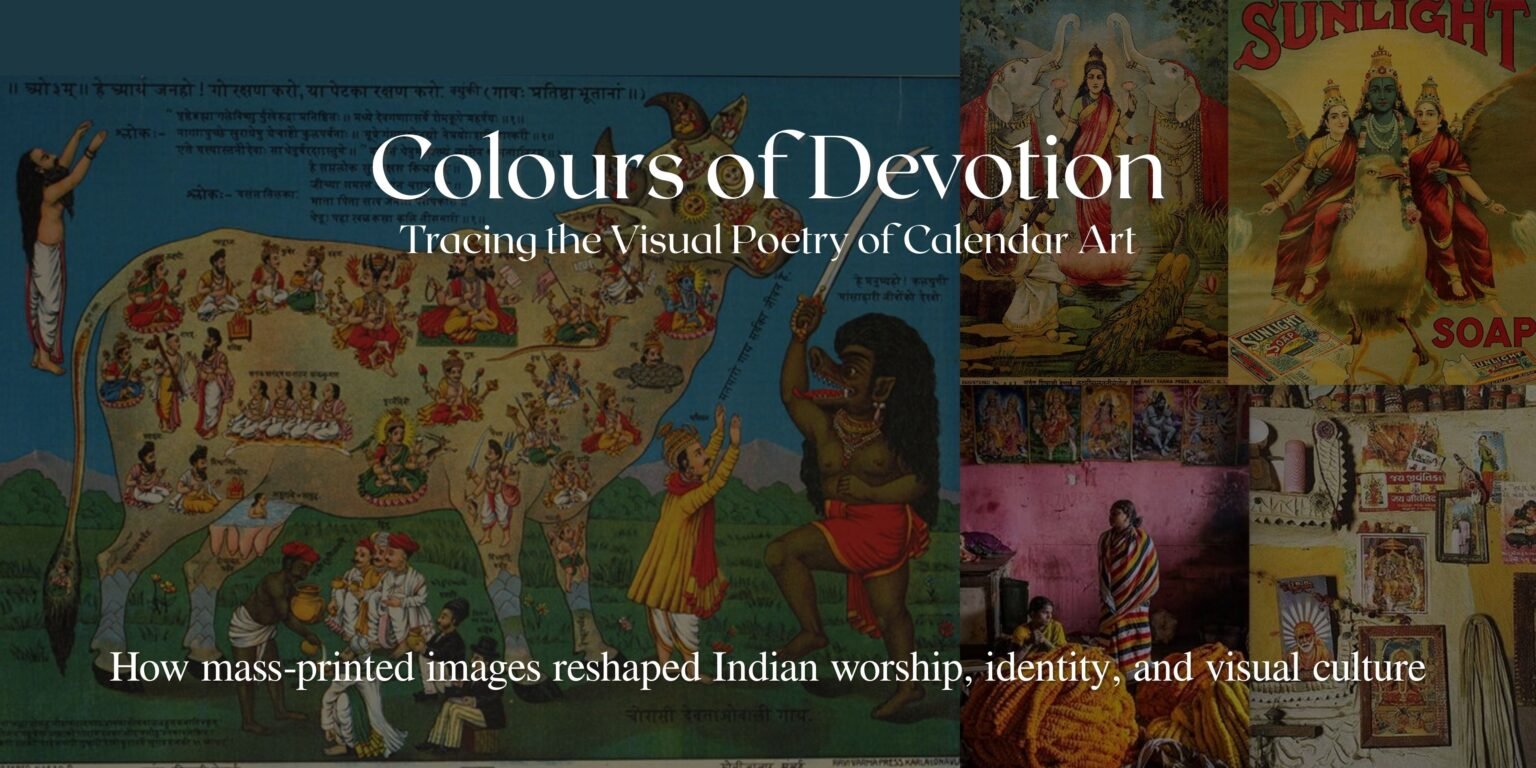

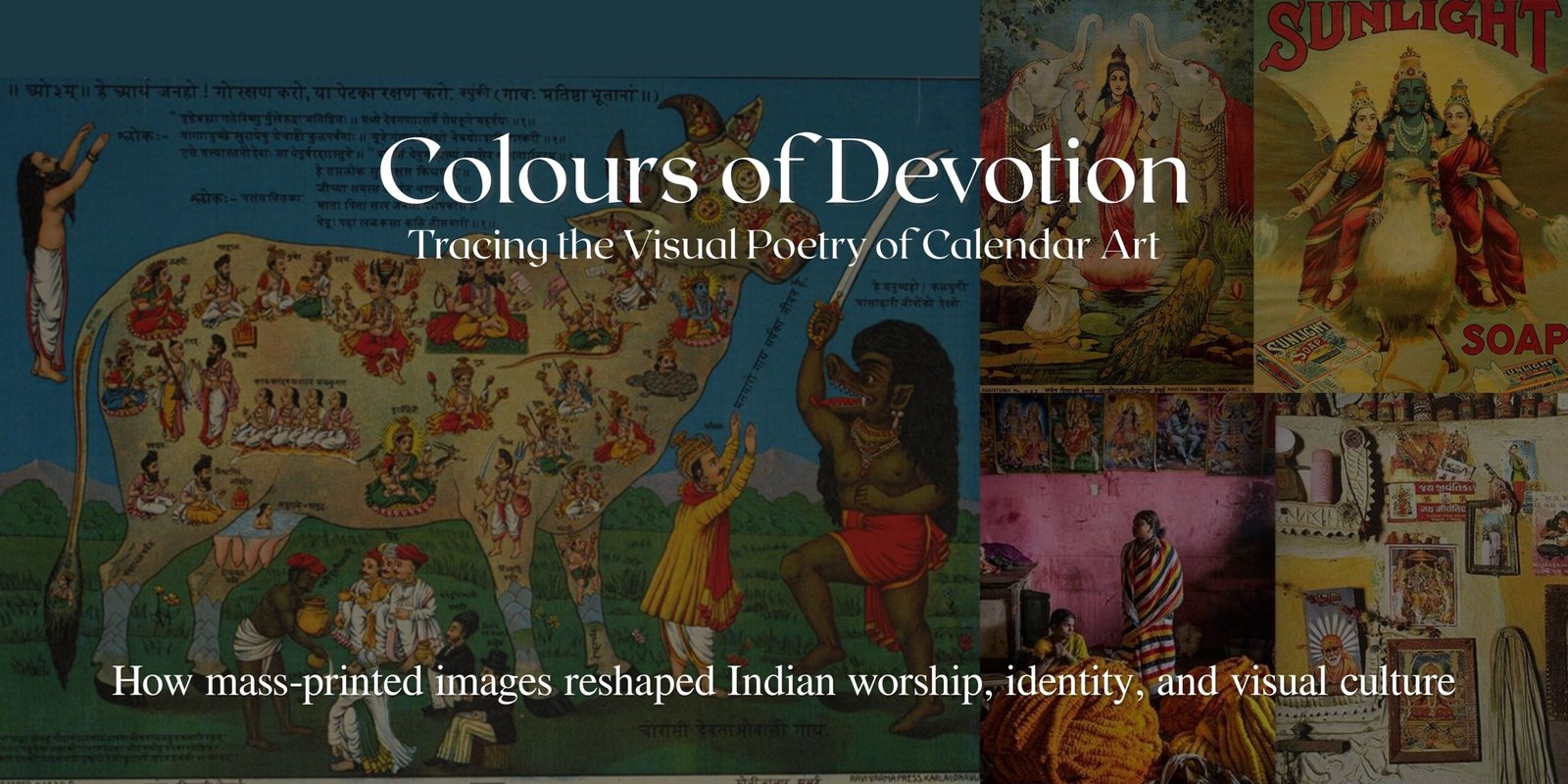

Calendar art is one of the most recognisable—and misunderstood—forms of Indian visual culture. Often dismissed today as “kitsch,” these mass-produced images once held extraordinary cultural power. They shaped how Indians worshipped, imagined divinity, constructed national pride, and decorated their homes. From Raja Ravi Varma’s pioneering lithographs to the million-print posters of the late 20th century, calendar art created a visual language that was democratic, emotional, and deeply embedded in everyday life.

This blog traces the evolution of calendar art in India—its origins, themes, cultural impact, and eventual decline—while highlighting why this colourful genre continues to fascinate artists, collectors, and cultural historians today.

The Birth of Calendar Art: Raja Ravi Varma’s Pioneering Vision

No discussion of calendar art can begin without Raja Ravi Varma, often hailed as the father of Indian calendar art. In the late 19th century, he pioneered the use of Western lithographic presses in India—a revolutionary step that changed the visual landscape forever. His oleographs and chromolithographs rendered gods and goddesses with breathtaking realism, making divine imagery accessible to millions for the first time.

In an era when most Indians had limited access to temple sculptures or illustrated manuscripts, Ravi Varma’s prints placed Lakshmi, Saraswati, Krishna, and Rama directly into the home. His blending of Indian mythological themes with European academic realism created a new aesthetic template—one that generations of calendar artists would later adopt, embellish, and mass-produce. This was not merely art; it was cultural transformation.

Beyond Varma: The Artists Who Shaped a Mass Visual Culture

While Ravi Varma laid the foundation, many artists expanded the vocabulary of calendar art. Names like Hemchander Bhargava, B.G. Sharma, L.N. Sharma, and Yogendra Rastogi became household favourites. Their artworks—highly decorative, devotional, and emotionally charged—could be found everywhere: in prayer rooms, shops, train stations, offices, and roadside shrines.

Their paintings were not confined to elite art circles; they existed in the living spaces of millions. These artists became visual storytellers for the masses. They standardized the look of gods and heroes, created moments of familiar devotion, and built a shared iconography recognizable across regions and languages.

In an age before smartphones and televisions, calendar art functioned as a powerful medium of communication.

The Themes That Defined a Nation’s Walls

Between the late 1900s and early 2000s, calendar art became one of the most widely consumed visual forms in the country. Its popularity revolved around four major themes, each reflecting a different cultural longing:

Religious and Epic Imagery

Most calendar art depicted scenes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas, and local legends. These images offered a simplified, emotionally immersive entry into sacred narratives. They also helped standardize the “look” of deities across India—something unprecedented in premodern visual culture

Patriotic Figures

Prints of nationalist leaders and freedom fighters—Shivaji, Maharana Pratap, Tilak, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Bhagat Singh, Subhash Chandra Bose—became symbols of anti-imperialist sentiment. Lithographs turned into political tools, carrying messages of unity and resistance.

Celebrity Pin-Ups

From the 1950s onward, glamorous photographs and paintings of Bollywood stars became popular calendar images. These “pin-up” calendars blurred the line between devotional and decorative desire.

Landscapes

Serene mountains, waterfalls, forests, sunrise scenes—these provided escapist fantasy, beauty, and calm, often deliberately avoiding human figures.

These themes shaped the aesthetic of middle-class Indian homes for nearly a century, embedding themselves into daily life and memory.

Private Devotion: How Calendar Art Entered the Home

Before the widespread circulation of printed images, worship in India was largely tied to public temples and community spaces. Calendar art changed this dramatically. With inexpensive, portable images readily available, households began setting up private shrines—compact puja corners adorned with mass-produced pictures of deities.

This shift transformed patterns of worship. The sacred moved from the temple to the living room.

Among these motifs, the cow became a powerful symbol of Hindu identity, especially during the 1890s when sectarian tensions rose. Its presence in calendars was not merely devotional; it reflected a deeper cultural and political assertion.

Calendar art helped encode these symbols into the national visual consciousness.

The Power and Paradox of Mass Reproduction

The introduction of lithographic printing democratized art like never before. Reproduction altered the artist’s status, making images more important than their creators. As millions of prints circulated

- the distinction between high art and mass art blurred

- artists lost individual recognition as prints overshadowed originals

- calendar art became both a unifying cultural force and a site of ideological tension

Some saw these images as unifying symbols; others viewed them as tools that reinforced religious or ethnic divides.

Walter Benjamin’s famous idea of the “loss of aura” in mechanical reproduction resonates strongly with the fate of Indian calendar art—visual power grew, but artistic authorship diminished

A Cross-Disciplinary Influence: Theatre, Photography & Film

The golden age of calendar art was deeply intertwined with other art forms. There was a constant give-and-take between printed imagery and performance culture.

- The Calcutta Art Studio’s chromolithograph Nala Damayanti (1880) predated the Star Theatre’s adaptation of the story in 1883.

- The visual aesthetic of Doordarshan’s Ramayan drew heavily from chromolithographic representations—and later, TV actors like Arun Govil and Deepika Chikhalia appeared in calendar-style devotional prints.

- D.G. Phalke, India’s first feature filmmaker, openly borrowed compositions and aesthetics from Ravi Varma’s prints.

Theatre fed into calendar art, calendar art influenced cinema, and cinema reshaped public imagination. Together they created a shared visual mythology.

From Revered to “Kitsch”: The Decline of Calendar Art

By the late 20th century, calendar art’s aesthetic began to lose ground. As photographic technology advanced, glossy photo-prints replaced painted imagery. Devotional consumers increasingly preferred “realistic” photographs of deities to highly stylized paintings.

Art historian Patricia Uberoi notes that while calendar art was once avant-garde, it is now regarded as authentic Indian kitsch—a nostalgic yet outdated form. What was once creative is now “sedimented,” overshadowed by more modern visual trends.

Today, calendar art is both an anachronism and a cherished cultural relic—rarely used for worship, but admired for its historical value and visual charm.

Why Calendar Art Still Matters

Even if mass-printed calendars have been replaced by digital wallpapers and framed photo prints, their influence endures. Calendar art:

- shaped India’s visual imagination for over a century

- offered accessible, democratic art long before the era of social media

- unified diverse audiences through shared imagery

- remains a critical chapter in Indian art history, visual culture, and political iconography

For collectors, artists, and scholars, these prints are invaluable records of how a nation negotiated faith, style, and identity.