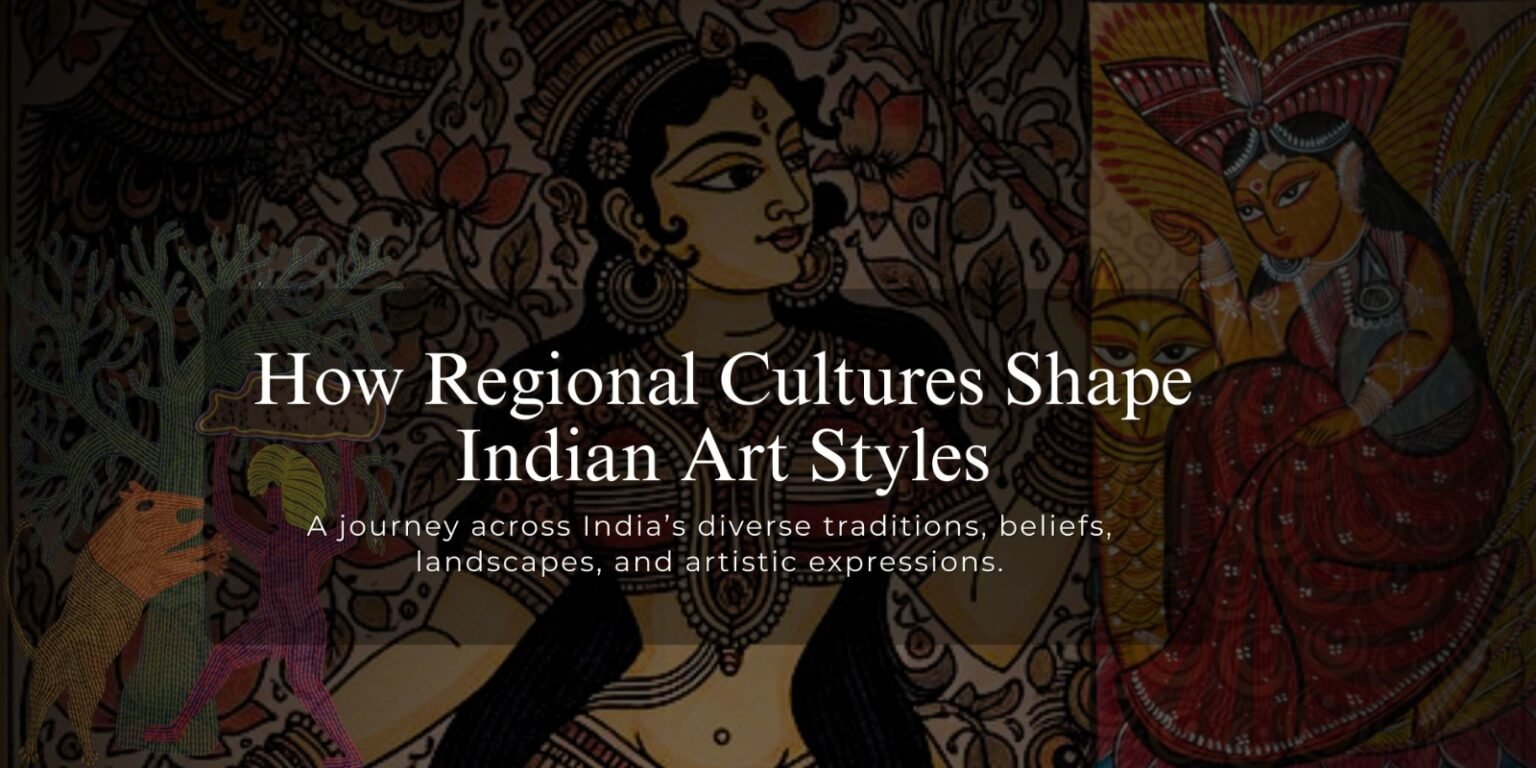

A Journey Across India’s Diverse Traditions, Beliefs, Landscapes, and Artistic Expressions

India’s artistic heritage is not a monolith but a kaleidoscope of regional idioms that embody local cosmologies, materials, rituals, and histories. Each form of traditional painting or craft reflects an intimate dialogue between communities and their environments, expressing cosmological beliefs, religious narratives, and social worldviews that have evolved over centuries. In tracing this cultural cartography, from the forests of Madhya Pradesh to the temple towns of Tamil Nadu and the valleys of Kashmir, we uncover not just aesthetic practices but living histories that continue to animate contemporary art and design.

Madhya Pradesh | Gond Art

Indigenous to the Gond communities of central India, Gond art is a vibrant testament to an animistic worldview in which flora, fauna, and spirit beings are intimately interwoven. Characterised by rhythmic lines, dots, and flamboyant colours, the motifs in Gond paintings echo the tribe’s sacred ecology, a universe where natural phenomena possess agency and narrative force. Animals such as deer, peacocks, and tigers are depicted with energetic contours and patterning that mimic indigenous rhythms of landscape and storytelling. Originally applied to walls and floors during ritual events, Gond painting has migrated to paper and canvas, thereby entering broader markets while still articulating communal epistemologies rooted in nature as kin.

Bihar | Madhubani Painting

In the fertile plains of Bihar’s Mithila region, Madhubani painting (also known as Mithila painting) historically emerged as women’s work embedded within homes and ritual cycles. Traditionally, women adorned newly plastered walls and floors for weddings and festivals, inscribing geometric patterns and mythological scenes that invoked auspiciousness, fertility, and prosperity. The iconography, gods, goddesses, birds, fish, and floral labyrinths, is rendered with bold outlines and flat planes of colour without empty spaces, a stylistic vocabulary that defies Western perspectival conventions. Over time, the tradition moved from vernacular surfaces to paper and textile, expanding its reach while preserving its symbolic density.

Odisha | Pattachitra

Along the eastern seaboard, Pattachitra paintings embody Odisha’s devotional and ritual imagination. The term literally means “cloth painting,” and its practitioners have long produced narrative visuals grounded in Jagannath temple culture. Rendered on cloth or palm leaves, these scrolls are distinguished by their fine brushwork, intricate detailing, and rich, flat colours. Mythological episodes, especially those of Krishna and Jagannath, unfold in successive panels, inviting viewers into sacred cosmologies through visual narration. The formal structure of Pattachitra, dense ornamental borders surrounding sequential narrative scenes, reflects an aesthetic logic deeply inseparable from ritual performance and temple pilgrimage.

Rajasthan | Miniature Painting

Rajasthan’s contribution to Indian painting, the miniature, flourished under the patronage of Rajput courts between the 16th and 19th centuries. Influenced initially by Mughal aesthetic syntax, Rajasthani styles developed distinctive regional identities (Mewar, Marwar, Bundi, Kishangarh), distinguished by meticulous brushwork, vibrant pigments, and refined detailing. These miniatures articulate courtly life, epic tales, romance, and heroic exploits, often juxtaposing human figures with stylised landscapes. Their compositional density and sumptuous colour harmonies not only reflect regal aesthetics but also embody an aristocratic worldview in which art served as a repository of memory, power, and narrative identity.

West Bengal | Kalighat Painting

By contrast, Kalighat painting, born in the cosmopolitan milieu around Kolkata’s Kalighat Kali Temple in the 19th century, offers a more urban and socially reflexive register. Initially produced by itinerant patuas (scroll painters) on paper, these works depict mythological figures and local life with bold outlines and expressive figures. Over time, Kalighat painters incorporated satire and social critique into their repertoire, portraying colonial encounters, domestic scenes, and social mores with incisive simplicity. In doing so, Kalighat painting not only served devotional functions but also mirrored the cultural reform movements and emergent urban consciousness of Bengal in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Maharashtra | Warli Art

In the tribal hinterlands of Maharashtra, Warli art conveys a strikingly minimalistic yet philosophically robust idiom. Using simple geometric forms, circles, triangles, and lines, Warli artists depict human figures engaged in farming, hunting, dancing, and festival rites against earthy red ochre backgrounds. The compositional economy, white rice paste against mud walls, communicates communal harmonies and cyclical rhythms of life. Warli art’s aesthetic could be understood as a visual equivalent of collective ritual performance, representing a worldview in which humans and nature participate in continuous, reciprocal cycles.

Tamil Nadu | Tanjore (Thanjavur) Painting

From the temple town of Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu comes Tanjore painting, a tradition steeped in South Indian devotional aesthetics. Characterised by rich jewel tones, gold leaf embellishments, and iconographies focused on deities, these paintings reflect the opulence and spiritual gravitas of Dravidian temple culture. Materials such as semi-precious stones and gesso relief lend a sculptural quality to the images, generating a visual language that enfolds reverence, ritual, and regal ornamentation. The intrinsic link between these paintings and temple patronage situates them within a broader sacred economy of worship and artistic devotion.

Kashmir | Papier-Mâché Art

Finally, the papier-mâché art of Kashmir illustrates the region’s history of cross-cultural convergence. Introduced to the Kashmir Valley in the 14th century by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani and his entourage of Central Asian craftsmen, this technique transformed hand-made paper pulp into decorative objects adorned with floral and geometric motifs. Characteristically colourful and finely painted, Kashmiri papier-mâché reflects both Persianate aesthetic influence and local craftsmanship. Today, it continues as a vibrant handicraft tradition, a symbol of Kashmir’s hybrid cultural legacies and artisanal ingenuity.

Culture as Formative Ground

What unites these disparate traditions is not a singular aesthetic but a plurality of epistemologies, each region’s art forms emerge from and contribute to specific cultural grammars. Whether rendered on temple cloth, village walls, or scrolls carried from hamlet to hamlet, these artistic idioms embody localized cosmologies shaped by landscape, ritual practice, and collective identity. For art advisors, collectors, and cultural institutions, understanding these regional genealogies is essential not only for appreciating artistic diversity but also for engaging ethically with India’s living artistic heritage.